By Yaldaz Sadakova

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

I got out of the subway and started walking on 34th Street.

Although it was the height of the Great Recession—December 2008—Manhattan looked festive.

Christmas lights and ornaments glittered everywhere. Christmas songs emanated from every store. Every shop window promised deep discounts.

It all felt cruel. The previous week I’d been laid off from my journalism job. Without any severance, without any notice.

I’d just paid my rent, which left me with $500.

There was no prospect of money coming in soon. I didn’t qualify for unemployment benefits because of the visa I held.

I walked into H&M and started looking for the sales racks.

I couldn’t afford to spend money on clothes. But I had an interview for a writing job with an NGO in two days, and I had nothing to wear.

I picked up a pair of black striped pants and a turquoise jacket. I already had one black jacket, but I’d read that you need to have at least two, because if they invite you for more interviews, you shouldn’t wear the same stuff; even if you’re poor, you should hide it.

While I was paying at the counter, I hoped I’d soon be able to get a return on my investment of $15.

The job interview went well partly because I didn’t have to mention my immigration status.

But I knew a time would come during my job search when I would be the chosen candidate, and then I would have to reveal the fact that I needed a complicated visa sponsorship.

After the interview with the NGO, I sent a follow-up email. A few days later, I tried to follow up on the phone.

As I was dialing the number, my palms sweaty, I prayed I’d get the hiring manager’s voicemail. I was desperate and self-conscious about being desperate. I feared this would show in a phone conversation.

I did get the voicemail. I left a timid apologetic message.

A week later, I got a canned rejection email.

Fried Plantains

I kept applying. I was applying for everything.

Journalism jobs. Communications jobs. Restaurant jobs. Flyer distribution jobs.

By now, I’d became a résumé and cover letter machine. I’d wake up at 8:30 a.m., make coffee, shower, and at 9:30 a.m. I’d start writing résumés and cover letters until late into the evening. That was my new full-time job.

I usually wrote the cover letters on the mattress in my nearly empty room. When my two roommates weren’t home, I worked at the kitchen table.

Our small, narrow kitchen had a window overlooking our own backyard and the backyard of our neighbor.

Throughout the day, the neighbor played loud bachata tunes that made me want to break into dance.

There was no way you could listen to this upbeat music and be sad. Life at her house seemed to be a party, free of job search anxiety.

Every ten minutes, the neighbor’s bachata was drowned out by the nearby A train hurtling to and out of Brooklyn. I lived near the Brooklyn border, in south Queens.

Our kitchen was often filled with the honey-like smell of fried plantains. My roommate Cardoza made them all the time.

He started sharing them with me when I lost my job. He also shared with me rice and beans with boiled yucca on the side as well as anything else he made.

If I wasn’t home or in the kitchen when he was cooking, he’d put my portion in a container in the fridge for me. When I showed up, he’d open the fridge and point to the container.

“Hilda! For you!” Cardoza couldn’t pronounce my name.

I was super grateful because I could only afford white bread with mayo.

Just a few months earlier, when I moved into this apartment, this man had been a stranger to me, but now he essentially gave me a small portion of his modest salary. He worked as a security guard in Manhattan.

Cardoza was from the Dominican Republic, but he’d lived in New York for years.

After I lost my job, my other roommate had offered to loan me money.

I declined. I was too proud. I also didn’t want the responsibility of repaying her.

I thought I’d try to manage with what I had. I’d been poor all my life; I was only 25, but I’d mastered the ability to live on next to nothing.

“Let me know if you change your mind,” she said.

Lucky Kids

Occasionally, I took a break from writing cover letters to read the news online.

I came across many articles about recent university grads who had moved back in with their parents because they could only find low-paying work or no work at all. This trend was presented as a negative development.

I sympathized with these American kids. I knew first-hand how hard it was to start your career in the middle of an economic meltdown.

But I also thought these kids were lucky. They had a place in the U.S. where they could live rent-free, and they didn’t have to worry about visas.

Even if they had to move to an American city they didn’t like and take a crummy job, they could resume their career building efforts when the economy improved.

Those kids were still in the race; they were just pausing. I was in danger of being thrown out of the race.

I didn’t have family in the U.S. that I could live with rent-free, and I had only a few months left until my visa expired. I had to make things work as soon as possible if I wanted to stay in the U.S.

My only other option was returning to my home country.

But I didn’t have the money for a plane ticket, and, more importantly, I didn’t want to return.

Bulgaria didn’t offer me the professional opportunities I wanted.

I longed for a journalism career, so I wanted to stay in New York.

I thought at the time that the world’s media capital was the only place with an abundance of interesting media jobs; the only place where I could do meaningful journalism and connect with like minds.

I also didn’t want to cover Bulgarian news, even though Bulgaria had important issues worthy of coverage.

I’d already spent 23 years in Bulgaria. I wanted to learn about the rest of the world.

And I feared returning to Bulgaria would undo all the effort I’d put into securing my Master’s degree from Columbia’s Journalism School; I could have gotten a job in Bulgaria without that degree.

If I went back to Bulgaria now, returning to New York in the future would be pretty much impossible. How could I find a job in New York all the way from Eastern Europe?

I didn’t begrudge the support those Great Recession kids received just because they had American families and American citizenship.

But I found it interesting that they took for granted—and even complained about—opportunities which foreigners like me would have jumped at.

Brooklyn We Run Hard

When I got too tired from sitting in front of my laptop, I went jogging. It was one of the few relaxing activities I could enjoy for free.

I usually ran down the nearby Jamaica Avenue, the J train clattering overhead on the elevated track.

Like a typical Queens thoroughfare, Jamaica Avenue offered a taste of the whole world: tacos, samosas, falafel, pizza, sushi, KFC and more.

I couldn’t afford any of those, not even KFC. But I loved the reminder they carried: everybody here is from somewhere else. Just like me.

During one of my runs, I followed the elevated J track so far into Brooklyn that I ended up on Fulton Street.

When I stepped onto Fulton, which was new to me, I felt like an explorer who had discovered some amazing faraway land. I’d literally run into Brooklyn.

That portion of Fulton resembled Jamaica: covered with graffiti and lined with ethnic mom-and-pops to produce a vivid worldly landscape.

The soft snowflakes, along with the endorphin from my run, made everything even more magical.

Things will work out for you, I thought as I admired the gritty Brooklyn landscape.

Passport Privilege

In early January 2009, I was invited to an interview in Brooklyn for a communications job.

On the day of the interview, I put on my newly-purchased striped pants and turquoise jacket and took the train to Brooklyn.

I got off the subway in Bay Ridge and started walking to the address. I caught a glimpse of the Verrazano Bridge and the expanse of water in the distance.

My insides stirred and expanded, the way they always did at the sight of water and bridges. I had a sense of unlimited possibility for a moment.

Things will work out for you, I thought.

The interview went well. I got invited for a second and a third one. Then I was asked to provide references.

Soon after that, the hiring manager—I’ll call him Tom—phoned me.

It was a late morning in early February. Big snowflakes were falling, covering the rows of decrepit houses outside my window with a white blanket.

I was sitting on the mattress in my room, writing cover letters, just in case.

“I wanted to let you know that we called your references, and they had great things to say. We were also very impressed with your writing skills and with your grit and attitude,” Tom said.

I’d mentioned during the interviews that I’d attended Columbia on a rare full scholarship, and that I was the first person in my family to go to college.

“We’ve decided to offer you the job,” Tom added.

I had to suppress a scream. I tightened my grip on the phone.

“That’s great news! I’m so happy to hear that!”

“Yes, I can imagine. In terms of compensation, we’re able to offer $40,000. How does that sound to you?”

“Oh, that sounds great!” I said.

At the job I’d been laid off from, I made $24,000. I’d never been offered this much money. I’d expected a lower number.

My mind immediately went to all the things I could do with $40,000.

I could start buying cheese and ham for my white bread sandwiches with mayo.

I could start using both the washer and the dryer at the laundromat instead of carrying my wet clothes back home to save money.

I could buy a few extra pairs of socks instead of washing my three pairs in the shower.

I could start saving money.

I accepted Tom’s offer on the spot.

When I got off the phone with him, I felt royal relief. I didn’t have to worry about food or next month’s rent anymore. And I didn’t have to write cover letters, at least for a bit.

I put on Aventura’s Obsesión—one of my neighbor’s top bachata tracks—and I did a little dance.

I pictured myself reading the paper while commuting to my new job in Brooklyn.

Then I pictured myself shopping on 34th Street for clothes for my new job without doing crazy math about every single dollar.

That evening, a friend took me to a hacks and flacks gathering in lower Manhattan. I was happy to get out of the house and celebrate my victory.

At the event, my friend introduced me as a journalist who was about to cross over to the dark side of communications. It was a nice evening.

But as I mingled in the crowded bar and sipped my cheap beer, I was aware that the hardest part about securing the Brooklyn job was still in front of me.

The company was now going to ask for my ID and for proof that I was legally allowed to work in the country.

I did have a valid work permit because less than a year earlier I’d graduated from an American university.

But that permit was going to expire in four months.

To stay with the company beyond that, I’d need an H-1B, a visa for high-skilled foreigners.

The H-1B application process was a nightmare.

A company had to sponsor you for it.

The sponsorship process required the company to first prove that it was unable to find an American to do the job.

Then the employer had to pay thousands of dollars for the application. The law didn’t allow visa applicants to cover the expenses.

Even then the visa wasn’t guaranteed.

Successful applicants were chosen in a lottery, and the demand for visas usually outstripped the annual supply of 65,000 spots.

I suspected most people who believed that America had to tighten its immigration rules—or that undocumented immigrants should have found legal ways to get in—didn’t know about all these draconian requirements and the high costs involved.

There weren’t many legal ways to get into America or to stay there. And the ones that existed…well, good luck with using those.

This is still the case.

The mere thought of explaining to the company the H-1B process—which remains as convoluted and rigid as it was in 2009—made my stomach contract.

I felt like a tremendous inconvenience.

I feared Tom, the hiring manager, would withdraw the job offer when he heard the full story.

He called me the next afternoon. I was sitting on my mattress, reading the news.

He said I had to sign the employment offer and provide HR with an ID before my starting date.

I couldn’t postpone this any longer. I had to tell him. My heart began pounding.

“Yes of course, I’ll provide the ID. I should let you know that I’m here on a visa, on a work permit. The thing is, my permit will expire in the summer, in July. But it can be renewed. As long as your employer sponsors you, you can renew your status!” I tried to sound as upbeat and breezy as possible.

“Oh, I had no idea that this is your situation! I have to admit I don’t know much about visas and permits,” Tom said.

Of course not, I thought. You’re American; you could afford to be unaware and advance your career in New York without any immigration hurdles.

“Okay, so that changes everything, I’m afraid,” Tom went on. “I wasn’t aware of this. It’s my bad. I should have asked about this earlier. But I don’t think we can work together. We don’t do visa sponsorships, unfortunately. In this economy, it’s out of the question.”

“Right, I understand. But you wouldn’t even need to sponsor me. I do have a valid work permit. I am currently able to work here legally.”

“Yes, but as you mentioned, that permit expires in the summer. We’re looking for a long-term employee. This is not a temporary position. We don’t want to go through the same process in the summer. I’m really sorry.”

He hung up.

I stared at the blue sheet covering my mattress. I was crushed.

The whole thing felt unreal, as if it was happening to somebody else.

This wasn’t a dream job, but it would have provided me with cash, which I needed urgently.

I had less than $400, and my rent of $550 was due in a couple of weeks.

Also, this job would have allowed me stay in New York for three more years. An H-1B visa lasted three years.

My plan had been to look for a journalism job during that time—for a job that would be willing to sponsor me for another H-1B visa because each H-1B was tied to the company which sponsored you for it. Leaving the company meant losing your visa.

That possibility, however distant, was now gone.

I was being thrown out of the race because of something beyond my control—my nationality.

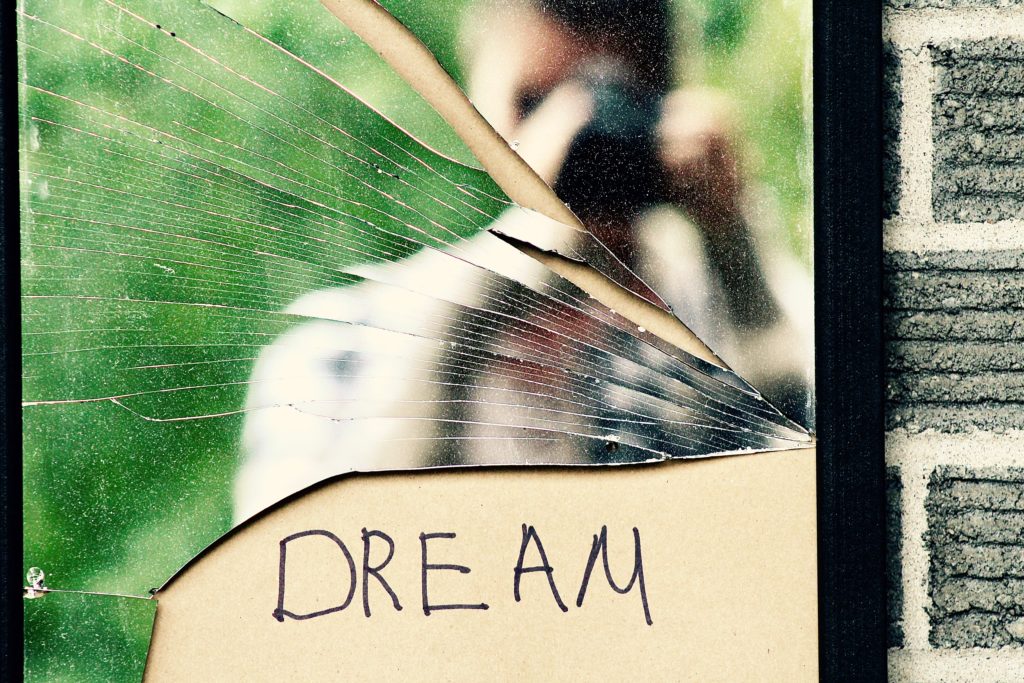

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

The implication of modern borders and global immigration rules became clear to me.

You’re not entitled to big dreams and wanderlust if you belong to the global underclass of non-Western passport holders. Shrink your dreams. Know your place. Go back where you came from.

For those who have the fortune of being born in a wealthy country, things are different. These lucky people can dream big.

They have amazing career opportunities in their home countries.

But if they choose to, they can work abroad without having to justify their global aspirations because nobody sees them as leeches.

Nobody describes their arrival in a foreign country as an influx.

Nobody views them as vermin that need to be contained.

When holders of nice passports take jobs abroad, there’s no talk of displacing local workers.

An American or Canadian banker can take a job at a financial firm in London, and nobody will say she’s stealing a job from British people or straining Britain’s resources.

In some instances, holders of nice passports still have to secure visas if they want to work abroad; they may still have to go through bureaucratic hell.

A Canadian citizen, for example, might need a visa to work in the U.S.—if their occupation isn’t on the list of professions which are exempt from the visa requirement.

But a French person can work in Germany, or elsewhere in Europe, without a visa.

In either case, they usually won’t be described as a burden.

Holders of nice passports can also travel visa-free to numerous locations.

Holders of nice passports can be expats, tourists and backpackers.

Holders of shitty passports have limited options in their home countries.

If they dare to have global career dreams, they quickly learn that traveling is restricted for them and subject to invasive rules and hefty fees.

And moving to another country? For shitty passport holders, this freedom is severely curtailed—and it’s considered acceptable only if they’re escaping bombs or persecution; only if they’re driven by desperation rather than dreams.

An Algerian whose life is not endangered at home but still wants to live in Europe would be seen as undeserving of the opportunity to do so. Because he’s an economic migrant and not a refugee.

His desire to move abroad will be questioned in a way an American’s desire never will be.

The American can dream. The Algerian cannot.

Shitty passport holders can only be immigrants, migrants or refugees.

And even then—regardless of whether they’re high-skilled or low-skilled, regardless of how much money they contribute to the economy—they’re accused of stealing jobs and sapping local resources.

It was after my phone call with Tom that I started to realize all this.

Then, several years later, I encountered these words in Philippe Legrain’s book Immigrants, and I got goosebumps.

“Why is the door open for American managers to run factories in Honduras but the door slammed shut for Hondurans who want to work for American factories? Why […] is free trade and the free movement of Western elites a wonderful thing but the free movement of everybody else unthinkable?” writes Legrain, who is an economist.

“Our new mobility, and that of products, money and information, jars with our efforts to hold people in poor countries in place. We sun ourselves on their beaches, peddle them aspirations to a better life through a soft drink or a baseball cap, broadcast alluring images of our munificent Eldorado—and then expect them to stay put.”

Although in 2009 I belonged to the underclass of shitty passport holders who were expected to stay put and who couldn’t easily move abroad, my passport wasn’t so bad when it came to travel.

Bulgaria had just become a member of the European Union, so I was able to visit other European countries without a visa.

But, unlike the citizens of wealthy EU countries, in 2009 Bulgarians weren’t allowed to work across Europe without a permit.

Bulgarians gained this right in 2014, seven years after joining the EU.

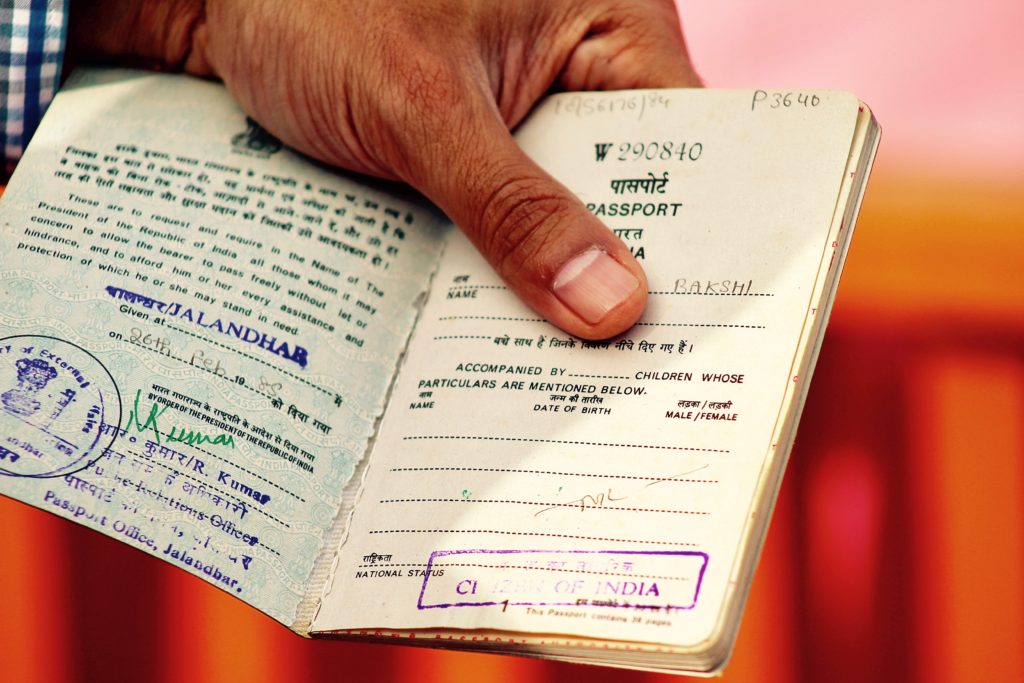

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

Half an hour after Tom withdrew the job offer on the phone, I emailed him. I was restless and desperate to do something, anything.

“I really wish that you would be fine with hiring me until July because I am confident that I can still make a contribution and efficiently perform all the tasks,” I wrote. “But I understand. If, however, you change your mind, please let me know!”

Then I messaged a Bulgarian friend in Florida to tell her what had happened.

She said I should file a complaint against the company because this offer withdrawal smacked of discrimination.

I decided to ignore my friend’s advice despite the fact that I was angry. Not so much with the company, but with the rules which prevented it from giving me a job I’d earned through fair competition, without any referrals or connections.

I was angry, but I didn’t think I had a legal case.

I didn’t think I had any rights in that specific situation, although I was vaguely aware that bias against job candidates based on their country of origin was illegal.

I didn’t know how to file a complaint either. I assumed—wrongly—that I’d need a lawyer, which I couldn’t afford.

I also doubted whether the complaint of a foreigner from a poor country nobody knew where to find on the map would be taken seriously.

Plus, I didn’t have time to deal with legal stuff.

I needed to find a job right away. My rent was due in two weeks, but I didn’t have enough money for it.

After I finished chatting with my friend, I went on Craigslist.

In the next two hours, I applied for every restaurant job in Manhattan that had been posted that day.

Meanwhile, I kept refreshing my inbox, hoping to hear back from Tom, hoping for some immigration miracle.

He never wrote back. ♦

ALSO READ:

Foreign, Poor and in the Ivy League

Shame and Self-Loathing in Brussels

Having a Precarious Immigration Status Makes You Vulnerable at Work