By Yaldaz Sadakova

A while back, a friend emailed me Ijeoma Umebinyuo’s poem Diaspora Blues.

So, here you are

too foreign for home

too foreign for here.

Never enough for both.

I’d never heard of Umebinyuo. But I loved the poem, which I later learned was part of her poetry collection Questions for Ada.

In just a few words, she’d managed to capture what it’s like to be an immigrant.

Then, last year, I came across Umebinyuo’s profile on Twitter. “Quietly sharpening the blades of my pen,” her bio said.

I followed her. She often shared poems from Questions for Ada. I loved them all. I ordered the book.

When it arrived, I saw it didn’t have a publisher’s logo. I checked the book’s Amazon description, and it said it was independently published.

I had no idea she had self-published it.

I’d read a few interviews with Umebinyuo about her poetry collection, and the fact that it was a self-published book was never mentioned. Nor had I ever seen her mention that fact on Twitter.

But wait a second, I thought, why should she clarify that it’s self-published? The discussion should be about the content, not about who published it.

I read Questions for Ada in one sitting. I found the poems in it relatable and rebellious. They were the poems of a young woman who had found her voice and power.

I underlined so many of them. This one, for example:

I have organized all my fears,

we are having a rally tonight.

Please, come, attend.

Until then, I’d been primarily exposed to poetry by white non-immigrant men who were older than me or dead.

It was enlightening to read poems by a Black millennial immigrant woman for a change.

Maybe I could do the same thing, I thought after I finished the collection.

I could self-publish my personal essays in a book. They’re already online. That way, I could reach immigrant readers who have never seen my work.

Every one of these evergreen immigration-related essays had received positive feedback from readers.

The kind of effusive reader feedback I’d never received for my journalism writing.

“I could totally relate to this” and “thank you for writing with honesty” were comments I’d gotten over and over.

Picking Myself

I should pause and explain why I chose to self-publish my personal essays here on Foreignish in the first place—instead of selling them to media outlets.

One reason was that I was wary of the so-called personal essay industry.

I had seen numerous calls for pitches from editors looking for personal essays.

But these editors always sought stories which had to fit parameters that were too specific and sometimes downright arbitrary.

Or they asked for essays that could be pegged to news developments.

My immigration experiences didn’t fit any of those parameters.

Even if I had been able to sell essays to outlets that didn’t have these super specific requirements, I would have still had to give up creative control. I didn’t want to do that.

As a journalist, I was comfortable with having my work edited.

But I knew that entrusting an editor with your journalism stories—stories which are meant to be impersonal even when you invest lots of emotional labor in them—is different from entrusting them with personal essays about your vulnerabilities.

I feared the possibility of an insecure editor who wasn’t doing creative writing of their own steamrolling over my personal stories to make up for their own creative constipation.

There was also the issue of the rates media outlets paid for long-form personal essays. If they paid at all, that is.

Back in 2017, when I started publishing my essays, those rates usually ranged from $50 to $150 per piece, which wouldn’t even begin to compensate me for all the work and the emotional labor.

Giving up the ability to have the final say about my personal stories and the legal rights to them for a paltry amount and the possibility of reaching a general audience didn’t seem like a good enough trade-off.

There’s another reason why I chose to self-publish my essays.

I was already a huge believer in what Seth Godin calls picking yourself.

What he means by that is taking initiative and circumventing the gatekeepers: taking the risk to do the creative work you want to do and bringing it straight to an audience you have cultivated—instead of sending applications so an institution can pick you and then give you the permission to do that work. (On its own terms, of course.)

So, doing things like creating and releasing an album without a record label.

Publishing a book without a book publisher.

Making a movie or a sitcom without a film production company.

Starting a radio show (aka a podcast) without a broadcasting corporation.

“It’s a cultural instinct to wait to get picked. To seek out the permission and authority that comes from a publisher or talk show host or even a blogger saying, ‘I pick you,’ ” Godin wrote in a famous blog post.

“Once you reject that impulse and realize that no one is going to select you—that Prince Charming has chosen another house—then you can actually get to work.”

DIY

When the time came to publish my personal essay collection—when I had enough content to fill a book of a decent size—I didn’t even consider approaching a traditional publisher.

Three years earlier, in 2016, I had shopped my first novel around, an immigration story set in Brussels, and I had collected nothing but rejections.

I felt exhausted at the mere thought of sending out queries once again on the off chance that I might get chosen.

I didn’t want to go through the same drudgery and disillusionment.

I was going to pick myself and publish this book on my own.

After all, the stories I wanted to include in that anthology had already been vetted by an entity whose approval is far more important to me than the approval of a random editor who lacks first-hand immigration experience.

The entity I’m talking about is, of course, my readers: my fellow immigrants.

Especially highly educated (millennial) female immigrants.

Especially highly educated (millennial) female immigrants who are writers and creators themselves—and who like to contemplate the big questions around borders, migration, belonging, identity, language and social justice.

So I got to work.

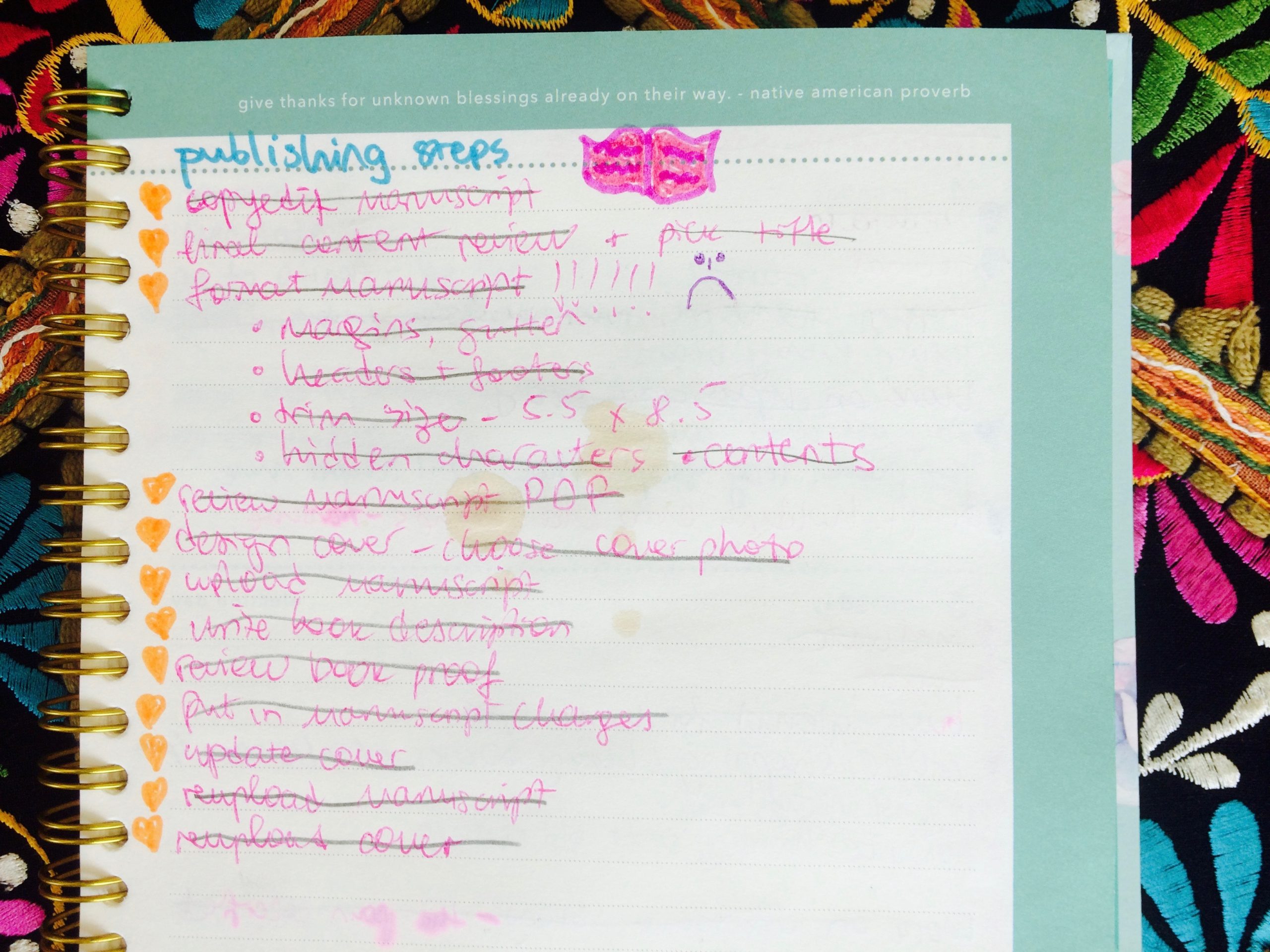

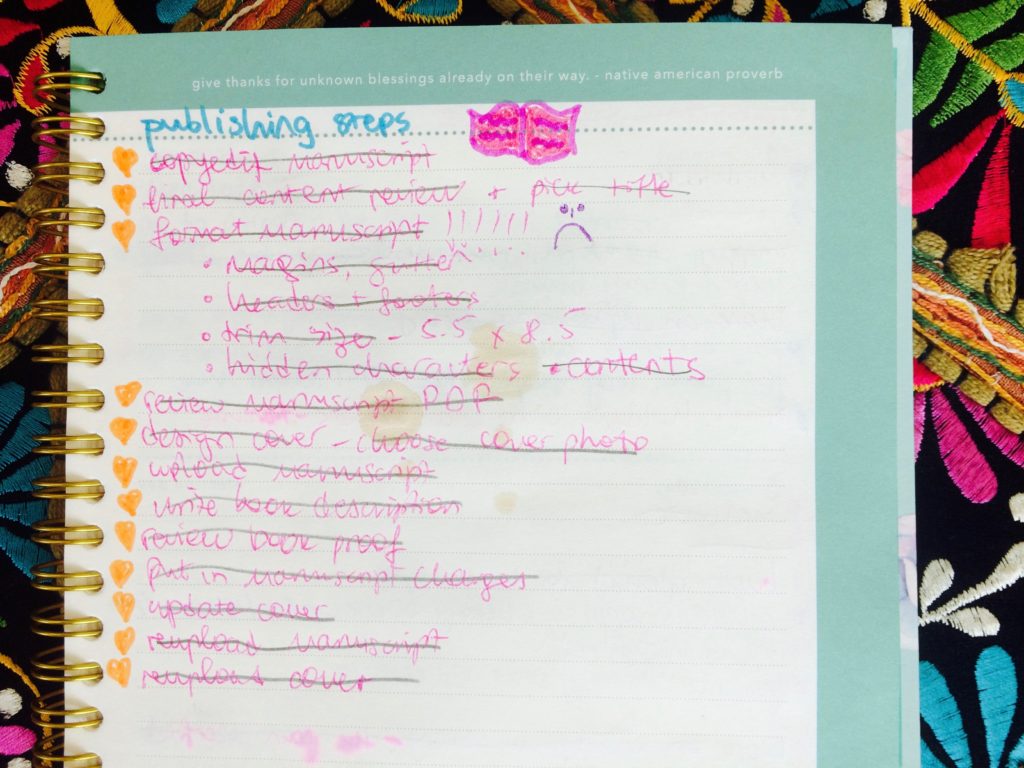

I copyedited and formatted my manuscript.

Indie writers are constantly advised against editing their own books. But I decided to rely on my own editing experience; I couldn’t afford an editor.

The manuscript was already pretty clean anyway. These stories had been published online.

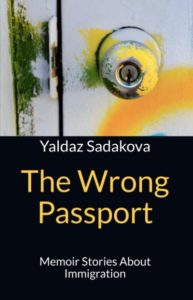

I came up with a book title: The Wrong Passport. Lack of passport privilege is a recurring theme in these memoir stories.

I designed the cover. That goes against the rules, too, because experts advise against designing your own book cover. But I couldn’t afford a designer.

Plus, Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform, which is what I used for my paperback, has a user-friendly Cover Creator, so I went with that.

Thanks to my experience with photography, I was able to take my own photo for the cover, instead of relying on a generic stock image of a passport.

I wanted an urban-decay type of image depicting a fence or a closed door to convey the ethos of the stories.

And I wanted a simple cover design.

Three years earlier, when I had made the Foreignish logo without any graphic design experience, I had learned that you should err on the side of simplicity with DIY design.

Next, I reviewed a proof copy of the book and added more changes to the manuscript and the cover.

Then I published the book.

Stigma

While I’m proud of my one-woman labor of love, I’m aware of the stigma attached to self-published books.

Some of that stigma has faded in recent years due to the fact that self-published books have improved in quality.

Still, an astounding number of people continue to believe that all self-published work is substandard. That self-published writers are amateurs driven by vanity.

But I think there’s just as much vanity in waiting for a gatekeeper to pick you as there is in the decision to self-publish.

Nothing satisfies a writer’s ego more than being able to say, “Oh look, an actual editor picked me, I have a legitimate book deal, and my book is going to be in bookstores.”

This is precisely why so-called vanity presses exist.

A vanity press is a publishing house which charges the author to publish their book—just so the author can technically have a publisher and create the impression of being picked by the establishment.

Don’t get me wrong. Although my readers’ approval is more important to me than an editor’s endorsement, I would still love to be able to say that I’ve been picked by an editor at a traditional publishing house.

That I have a book deal.

That a book of mine will be in bookstores.

Maybe one day all this will happen for me.

Or maybe it won’t.

Traditional publishing is extremely competitive.

It’s also biased against diverse writers like me who want to tell stories which are considered too specific for a wider audience.

For example, traditional publishers don’t seem very interested in books about people from poor countries with non-English names dealing with issues such as immigration bureaucracy and institutional discrimination.

How frequently do you encounter books like that, fiction or non-fiction?

This is something critics of self-publishing often ignore: the fact that with traditional publishing, the odds are stacked against diverse writers with niche stories. Especially if those writers are unpublished.

For many diverse writers, the only route to publication is self-publishing.

Shaming us for choosing that route and labelling our work illegitimate simply because it hasn’t been endorsed by the establishment marginalizes us even further.

So, yes, I might never get picked by a traditional publisher.

Will I be disappointed if that happens? Of course.

But I can’t let that possibility stop me from sharing my work—including my political novel about immigration, which I still want to put out into the world, once I find the time to revise it.

As Julia Cameron pointed out in The Right to Write, “Your odds of being published become one hundred percent the minute you are willing to self-publish.”

Several of her books started out as self-published manuscripts, including The Artist’s Way, which became wildly successful and of which I own a marked-up copy.

“I believe that if one of us cares enough to write something, someone else will care enough to read it,” Cameron said.

I agree with her. ♦

NOW READ:

The Shame of Forgetting My Mother Tongue