By Yaldaz Sadakova

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

Your stickiest identity issues can resurface while you’re ordering eggplant in a shawarma restaurant.

That’s what happened to me a few years ago in Toronto, where I live.

While the restaurant owner—a middle-aged man with a fish tattoo on his forearm—was packing my order, I started talking to him in Bulgarian. I’d just heard him speak Bulgarian with someone else.

After chatting for a few minutes, it became clear that not only were we both from Bulgaria, but we also belonged to its Turkish minority. He switched to Turkish.

I understood what he said, but I responded in Bulgarian every time. Eventually, I asked him to switch back to Bulgarian. I explained I’d forgotten Turkish because I hadn’t practiced it for more than 10 years.

“What do you mean you forgot your mother tongue?” Mr. Turkish Shawarma protested. “A person can’t forget their mother tongue!”

The implication was clear. I was a traitor to my heritage, while Mr. Turkish Shawarma was an exemplary Turk. He’d been in Canada for years, yet he still spoke fluent Turkish.

Angry and ashamed, I quickly left with my roasted eggplant.

A Forbidden Language

Turkish is for me what linguists call a heritage language—it’s the language of your parents, and it’s a minority language you speak primarily at home because it’s different from the official language of where you live.

Turkish was also a forbidden language.

Bulgaria’s Communist regime banned Turkish just before I started learning it as a toddler in the mid-1980s.

The outlawing of Turkish was part of an oppressive assimilation campaign the regime carried out against Bulgaria’s Turkish minority, which, like my family, is primarily Muslim. The Communists wanted to create a homogenous Christian nation.

Bulgaria’s Communist regime began forcible assimilation attempts soon after it came to power, in 1946. But the campaign started in earnest in December 1984.

As part of that assimilation campaign, the Communist government also forced all citizens of Turkish descent to change their names.

Within three months of December 1984, often at gunpoint, 840,000 Bulgarian Turks had to renounce their Turkish names, mainly of Arabic origin. They were forced to replace them with Bulgarian ones, which are mainly Slavic or Christian.

Those who protested were killed or imprisoned.

For my family, it happened on a weekend morning, when armed police officers came to our house. At the time me and my mom, a single parent, lived with my grandparents in a poor predominantly Turkish neighborhood.

My grandparents were driven to the police station. There, they dropped off their passports, which were no longer valid because they contained their Turkish names. They quickly picked random Bulgarian names. Their new passports, with Bulgarian names, would become available within days.

When my grandparents returned home that morning, my mom was taken to the police station to register her new name and mine. Like my grandparents, she picked random Bulgarian names.

“It didn’t matter what the names were; we never saw them as our real names—just our names in front of the state,” she told me recently.

From then on, like other Bulgarian Turks, I had two names: an illegal Turkish name at home and a Bulgarian name outside of home. The Bulgarian name always felt fake.

The initials of my Bulgarian name were stitched on the collar of my kindergarten uniform.

The practice of Islam was also banned in Bulgaria as part of the Communists’ assimilation campaign. Mosques were shuttered. Wearing headscarves and other Islamic attire became illegal.

In 1989, Bulgarian Turks started protesting against the government’s assimilation campaign. The police responded with beatings and shootings.

After the protests died down, the government expelled 360,000 Bulgarian Turks to neighboring Turkey.

Another reason for the deportations was the regime’s fear that Bulgaria’s ethnic Turks might one day outnumber ethnic Bulgarians. (Funny how repressive governments always seem to have that fear about minorities.) Turks made up about 10 percent of the population.

At the end of 1989, Bulgaria’s Communist regime disintegrated. It took the post-Communist Bulgarian government more than 20 years to formally recognize the 1989 expulsion of Bulgarian Turks as ethnic cleansing.

After Communism collapsed, Bulgarian Turks got their names, culture and religion back.

The name I got back was mangled. It didn’t feel like my own any more. Imagine Jane Paterson becoming Djein Patersanova. That’s what happened to my name.

My last name received an “ova” suffix, which is typical for Bulgarian names, but not for Turkish ones.

My name was also misspelled in my IDs. The Bulgarian alphabet doesn’t have certain letters that are present in the Turkish alphabet. Some of those unique Turkish letters appear in my Turkish name, so the Bulgarian spelling of my name was just an approximation of my actual name.

My lost-in-translation name felt neither Turkish, nor Bulgarian. Just an ugly hodgepodge.

Improving My Turkish

The Communists’ assimilation campaign made my family, especially my grandparents, even more adamant that I should speak Turkish. This is despite the fact that my parents as well as grandparents and great-grandparents on both sides were born and raised in Bulgaria.

Our roots in Bulgaria went generations back, but there was always a distinct feeling in my family that we were not Bulgarian.

So, for my grandparents, not speaking Turkish was tantamount to betrayal.

But I was never able to learn Turkish properly.

When Communism collapsed, I was about to start second grade—I’d already learned to read and write in Bulgarian.

Because Turkish had been banned until then, I could only learn it from my family. I couldn’t write or read it. My vocabulary was limited. My grammar was poor. When I spoke it, I threw in Bulgarian words and grammatical structures. Linguists call this practice of mixing languages code-switching.

My Turkish improved in third grade thanks to a yearlong after-school Turkish language program. During my weekly classes with other Turkish kids, I learned the Turkish alphabet and some grammar. I learned to read short simple sentences. My vocabulary expanded.

In my teens, I started watching Turkish soaps on satellite TV. Most Turkish households in Bulgaria acquired satellite dishes in the 1990s. Our satellite dish also allowed me to listen to Turkish radio.

My favorite radio show aired every day after midnight. It was a show about spirituality with a New Age slant. Although I had to go to school, I stayed up until 3 a.m., listening to the female host read poems and discuss the meaning of life in her charming lisp. I learned many formal Turkish words.

It was not because of any desire to improve my Turkish that I watched and listened to these shows—although my grandparents sometimes reprimanded me that my Turkish wasn’t good enough.

I followed these shows because I loved them; they just happened to be broadcast out of Turkey. Even in the 1990s, Turkish TV and radio offered entertaining programming 24 hours a day. Bulgaria at the time had only two channels which broadcast a few hours a day.

Throughout the 1990s, we made several summer trips to Turkey. We stayed with my mom’s sister and her husband—Bulgarian Turks who immigrated to Turkey in the 1970s. They had a Turkish-born daughter just a few years younger than me.

With each visit to Turkey, I learned new words and grammatical structures. But I still spoke Turkish with a Bulgarian accent. My Turkish-born cousin loved making fun of my accent. That stung. In the eyes of Turkish-born people, I was not Turkish enough.

And despite all the progress that I made with Turkish in my teens, I still couldn’t read or write it freely. I still had to think before saying certain things.

I was much more comfortable with Bulgarian, even though I started learning it a couple of years after I began learning Turkish. Because I was schooled and immersed in Bulgarian, it felt like my de facto native language.

So I spoke Bulgarian with my mom, using Turkish only with my grandparents and older relatives who insisted on speaking Turkish.

But the fact that my mother tongue was a foreign language to me made me feel like a freak.

Only when I started writing this piece did I learn that it’s not unusual for kids who are heritage speakers to struggle in their mother tongue.

“It is more common for such children to use their native language in ways that are typical of second or foreign language learners than in ways that are characteristic of native speakers: They will often have a strong foreign accent and not fully master some or many of the grammatical rules of their language,” Monika Schmid, a professor of linguistics at the University of Essex, notes on her website.

When I called her for an interview, Schmid explained that even if parents use the heritage language with the child, the child may still not learn it properly. “Sometimes children refuse to speak it, or they don’t want to be different from others.”

And Schmid said that being good at languages doesn’t necessarily help with becoming proficient in your heritage language.

Regardless of the reasons, when people have a poor command of their heritage language, they often feel guilty and inadequate, Schmid told me.

She said this feeling is more pronounced for heritage speakers who are members of visible minorities.

“You feel that visually you stand out, and you’re classified as belonging to a different population, but you…can’t feel [like] a part of that other community because you don’t speak the language.”

The Language of Shame

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

At school, I mentioned my love of Turkish TV and radio to just two friends. I kept quiet about my trips to Turkey.

I was the only Turkish kid in class—and one of the few Turkish kids in the entire school, so I didn’t want my otherness to attract further attention.

Plus, Turkish language and culture weren’t something I wanted to associate myself with.

Bulgaria was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1396 to 1878. This period was the main topic of my history and literature classes.

Year after year, I learned about the numerous atrocities of Ottomans, who were usually portrayed as barbarians.

They massacred Bulgarians. They imposed exorbitant taxes on them for being a non-Muslim minority and restricted their rights. They forcibly converted some Bulgarians to Islam. They even kidnapped some young Bulgarian boys, converting them to Islam and then enlisting them in the Ottoman army.

All of these atrocities did happen. I don’t want to downplay them.

But while I was learning about them, nobody—not the textbook writers, not the teachers, not my family—ever made a distinction between the rulers of the defunct Ottoman Empire and modern Bulgarians of Turkish descent.

I would have appreciated the distinction.

In its absence, I internalized the belief that cruelty was part of my DNA. That I was deeply flawed in a way ethnic Bulgarians were not. That I didn’t have the right to be where I was. That Bulgarians would never see me as one of them. That the best I could ever be is a Bulgarian with an asterisk.

My feelings were exacerbated by the anti-Turkish, anti-Muslim sentiment that has always existed in Bulgaria. You won’t see the sentiment among all Bulgarians—and sometimes it’s subtle or unconscious. But it’s there.

“She’s Turkish, but she’s very nice.”

“She’s Turkish, but she’s educated.”

“She’s Turkish, but she’s very clean.”

I’ve heard statements like that.

I learned to use the words Turkish and Ottoman interchangeably, like my textbooks and teachers did.

I learned to associate Turkish and Ottoman with words like barbaric and subhuman.

I learned to express anti-Turkish views in my school essays.

“This is a seminal poem by a Bulgarian revolutionary hero who courageously fought the barbarian Turks and tried to liberate Bulgarians from Ottoman Yoke.”

“The masterpiece of this talented Bulgarian writer helped Bulgarians keep their identity intact at a time when the Turks were trying to impose their savage culture.”

By the time I was in high school, I was deeply ashamed of my Turkishness. I wanted to shed it. I wanted nothing to do with it. Nothing.

One time I was hanging out with two Bulgarian high school friends in our living room. My mom and my grandmother were in the next room. At one point, they moved to the hallway and started conversing in Turkish. I wanted nothing more than to disappear, to undo this moment. Now my friends knew that we spoke Turkish at home—that we were Turkish for real.

Another time a Bulgarian friend asked what the names of my grandparents were. My cheeks burned with embarrassment as I reluctantly uttered their Muslim names—Ahmed and Ayşe.

Losing My Turkish

The last time I spoke Turkish was in 2003, after my first year in university. I spent the summer working in the United States to make money for school.

One of my coworkers was a university student from Turkey called Yılmaz. My spoken Turkish at the time was decent enough that Yılmaz and I could communicate easily. We became friends.

After Yılmaz, I stopped speaking Turkish. I had no reason to—I didn’t encounter any Turkish people.

It was only in 2007, when I moved to New York City for graduate school, that I met someone else from Turkey, a classmate.

By then, I’d pretty much lost my Turkish.

I could understand it if the content wasn’t too complicated, but I couldn’t respond. I still knew many words, but I couldn’t put them together in sentences. The grammar escaped me. Anything other than uttering simple phrases like “How are you?” was beyond my abilities.

When I met my Turkish classmate, I sheepishly explained in English that I’d lost my Turkish. I expected her to be judgmental, but she never said anything. I didn’t feel like practicing Turkish with her. I was too embarrassed about how rusty my Turkish was. I was grateful she never pressed the issue.

So, when we ran into each other on campus, we always spoke English. When we had to work together on a school assignment for several weeks, we also stuck to English.

After graduate school, I started actively avoiding Turkish people in New York.

When I moved to Brussels a couple of years later, I tried to do that, too. But avoiding Turkish people in Brussels is hard because the city is home to a large Turkish community.

So every time I went to shawarma restaurants and heard staff speak Turkish, I ordered in English and didn’t let on that I understood them. I worried they’d start a conversation, and I’d be found out. She’s not really Turkish! She doesn’t even speak Turkish! She’s a fraud! I could totally imagine them thinking that. And I didn’t feel like explaining why I didn’t know Turkish.

These days, my Turkish is still so poor that I don’t even contact my cousin in Turkey, the one who used to tease me about my Turkish. On her birthday, I just go to her Facebook wall and copy-paste generic wishes in Turkish already posted by others. Then I add emojis. Thank God for emojis.

But it sometimes bothers me that our close childhood relationship has now devolved into exchanging generic Facebook greetings once a year.

I’d actually love to visit her in Istanbul. I’d love to lounge with her in sidewalk cafés and stroll along the Bosphorus and play with her baby. But then I always decide against it. How will I talk to her? Even if her English is good enough, which I don’t think it is, I’ll be too embarrassed that I forgot Turkish.

And because my Turkish is so poor, when relatives speak to me in Turkish during my visits to Bulgaria, I always respond in Bulgarian. They get the hint.

Except for one of my aunts. One time she called me and started speaking Turkish. I kept responding in Bulgarian, but she was hell-bent on speaking Turkish although her Bulgarian is excellent.

In the middle of the conversation, I “accidentally” hung up. When she called again, I said: “Hello? Hello? I can’t hear you. You’re breaking up. Hellooooooo?” I could hear her perfectly well, but I hung up again.

I felt like an idiot. And like a powerless child, though I was in my late 20s. I didn’t have the guts to tell my relatives the truth.

Even though for years I assumed that I lost my Turkish because something is wrong with me, forgetting your first language is actually a common phenomenon. Linguists call it language attrition.

Common signs of attrition include trouble remembering certain words, speaking hesitantly, pairing words in odd ways, developing a foreign accent and “coming to feel like a foreigner in your own mother tongue,” Schmid, the University of Essex linguistics professor, notes on her website.

Although language attrition is common, “it is usually both unexpected and deeply upsetting, and the research on it is very sparse as compared with the vast field of research on second language development,” Schmid says on her website.

The level of first language attrition depends on your age and on whether you’re a heritage speaker.

“There are strong indications that a native language will stabilize around age 12. If a child is removed from the native language community before that age, he or she can forget this language to a large extent, or even entirely. The same is true for children who are born to families that speak a different language than the one used in their surroundings,” Schmid explains on her website.

Losing Some of My Bulgarian

Photo by Yaldaz Sadakova

I’ve been living outside of Bulgaria for more than a decade. At this point, I’ve lost some of my Bulgarian, too.

But because I stopped using Bulgarian only after I’d mastered it and after I’d turned 12, I haven’t lost it nearly as much as I’ve lost Turkish.

“If you have learned your native language fully from childhood and speak it until you are about twelve years old, it will normally be quite stable and resist erosion”—although you will still experience some attrition symptoms, Schmid says on her website.

“Any problems that you may encounter are more likely to be the result of a competition for attention and selection that takes place in your brain between your two (or more) languages.

“All of the different languages that we know are always to some extent ‘active’ in our mind. The more active a language is (that is, the louder it is screaming for you to pick it), the more likely it is to be selected by accident, even if you were really intending to use the other one. This state of ‘activation’ depends not only on how often you use a language, but also on how recently you have last used it.”

And whether you use your first language at work while you live abroad could be another factor in the level of attrition.

Research conducted by Schmid and other linguists shows that immigrants who use their first language for professional purposes are less likely to experience massive attrition.

“But it’s also possible that if you don’t use it at all, you’re just going to be absolutely fine. I have seen that as well,” Schmid told me.

Still, why is it that you’re less likely to experience attrition if you use your first language for work because, for example, you teach your native Arabic in Canada?

Schmid has a theory. In professional circumstances, it’s usually inappropriate to mix your languages—something bilinguals often do when they talk to family and friends. This code-switching prevents you from inhibiting your second language.

When you’re regularly in professional situations where you can’t code-switch, you become better at inhibiting your second language and preventing it from interfering while you’re speaking the first language, Schmid told me.

“That muscle that you’re training is the muscle that helps you go on using your first language without it really becoming affected by the second language.”

Because I don’t use Bulgarian for work, I rarely read in it, and I only speak it occasionally, my vocabulary has shrunk.

When I have to speak Bulgarian or type a message in Bulgarian, I often pause because I don’t remember certain words. When I talk to Bulgarians who know English, I throw in a lot of English words. And if I have to explain something more complex, I switch to English entirely.

I also switch to English if I feel silly expressing something in Bulgarian, usually something deeply personal, like my desire to get better at self-love and improve my meditation practice.

These aspirations sound pretentious and self-indulgent if I try to express them in Bulgarian. Maybe because self-love and mindfulness aren’t mainstream concepts in Bulgaria the way they are here in the West.

Bulgarian society remains less individualistic and poorer than Western societies, so a number of Bulgarians still associate self-love and mindfulness with selfishness, narcissism and luxury.

I can imagine those Bulgarians saying, “My electricity bill is astronomical, and you’re telling me I should just love myself and meditate?”

Because I feel self-conscious about conveying certain things in Bulgarian, I see Bulgarian as a language that is no longer able to accommodate all aspects of my personality.

I feel like I’ve outgrown it.

When I speak it, I often feel like I’m reverting to my awkward, ashamed self. In Bulgarian, I’m once again the kid with the tainted heritage; the unpopular teenager with ill-fitting baggy clothes and a boyish haircut.

Also, when I speak or think in Bulgarian, I display unsavory Bulgarian traits that I manage to tone down when I function in English—traits like pessimism, incessant complaining and a victimhood mentality. No wonder my Bulgarianness often feels like a liability to me.

Maybe that’s why the deterioration of my Bulgarian doesn’t pain me.

When I speak English, I feel like a smarter, more eloquent version of myself. I feel like more things are possible.

English has allowed me to reinvent myself and see things through a wider, more international lens.

It’s the language in which I have gotten to know myself better. It’s the language in which I’ve started to learn self-compassion. It’s the language in which I discovered my purpose—writing.

English has provided me with a clean slate, while my first two languages have burdened me with political and historical baggage.

English is the balm for the wounds Turkish and Bulgarian have inflicted on me.

Although I speak it with a slight accent, English belongs to me. But not completely. It’s not my mother tongue, and I only started learning it in late childhood, so I feel like I can’t claim it fully.

I can’t claim my first two languages either: they’ve atrophied. And they’ve never felt completely mine to begin with. Turkish felt like a foreign language from the start. Bulgarian was the language in which I learned that my heritage is shameful, and I don’t have the right to be where I am.

For all intents and purposes, I don’t have a language that is all my own. I feel like a homeless person in the world of language. At times, this makes me feel unmoored and inadequate, especially since words are my passion and profession.

I shared this sentiment in a phone interview with Aneta Pavlenko, a professor of applied linguistics at University of Oslo’s Center for Multilingualism in Society across the Lifespan.

Pavlenko said feeling the way I do is normal given the monolingual standards of modern society.

Until the 18th century, for millennia, bilingualism and multilingualism were common everywhere. Take the Roman Empire, where Latin and Greek coexisted with other local languages.

“What happened to us in the 19th century was the ideology of romantic nationalism that equated one people with one nation with one language and highlighted the differences between us, making monolingualism comfortable and desirable. So monolingualism became the standard against which everything is now measured. And with this measure, we don’t measure up,” Pavlenko told me.

Why Some People Feel Different When They Switch Languages

Just like with the issue of language attrition, I used to think that feeling like a different person when switching languages was something unique to me—a certain lack of centeredness and schizophrenia that only I possessed.

But that, too, is a common phenomenon.

Between 2001 and 2003, Pavlenko and another linguist, Jean-Marc Dewaele, asked 1,039 bilinguals and multilinguals online if they sometimes felt like a different person when they used their different languages. That research was published in Bilingual Minds, an academic anthology edited by Pavlenko.

Sixty-five percent of respondents, who ranged in age from 16 to 70, said that they did sometimes feel like a different person when they used their different languages.

One respondent wrote: “It’s like you conform yourself to the way the native speakers talk and express themselves which is not necessarily the same as yours. For example the way the Greek people speak is very lively and very expressive. If I were to speak in the same way in English (or even German & French) people would misunderstand me and misinterpret my intentions – as it has happened many times.”

Another respondent said: “I don’t feel quite real in German sometimes – and formerly in French and Russian. I feel I’m acting a part.”

Yet another respondent, who reported feeling different in her different languages “to a certain extent,” said: “I feel more at ease speaking in my mother tongue. It’s like being at home with all the usual familiar worn and comfortable clutter around you. Speaking the second language is like being you but in someone else’s house.”

When bilinguals feel like they slip into different selves in their different languages, it’s usually because they learned their languages at different times, while living in different countries and in different contexts, Pavlenko told me.

She explained that for bilingual non-immigrants who use both of their languages in the same environment, this feeling likely doesn’t exist. For example, an English speaker born and raised in Canada with knowledge of French probably doesn’t feel like a different person when she switches from English to French.

Learning your different languages at different times determines your degree of emotional connection with those languages—a major factor in feeling like a different person across your different languages.

“It appears from recent research that after we pass the teenage years, we no longer form language-emotion connections that are as deep and profound as the ones formed in childhood. This is why taboo words and swear words of second and foreign languages do not affect us in the same way they do in the native language,” Pavlenko told me.

“So, given that the emotional connection is not as profound, we basically feel less of a connection and a more disembodied self, so to speak, in a second language. It’s easier to hurt us, it’s easier to rile us in a first language. And in the second language, people sometimes feel like they’re wearing a mask.”

Learning your different languages in different contexts means that the same words in each language will evoke different autobiographic memories, contributing to feeling different across your languages.

“The church is not the same as église, and it’s not going to [evoke] the same images as the Russian word tserkov,” Pavlenko told me.

Although bilinguals often perceive their first language as more emotional, Pavlenko acknowledges that some, like me, prefer their second language for emotional expression.

This is “because they grew up in a tradition of a ‘stiff upper lip’ or because they mainly live and interact in the realm of a second language,” she writes in Bilingual Minds. Also, people who “negotiate relationships or raise children in the second language often view it as very emotional and meaningful.”

And in some cases the second language is a form of liberation.

Studies in bilingual psychoanalysis from the 1980s and 1990s confirm that for patients who have learned their second language in late childhood or adulthood, words from the first language can trigger “painful, traumatic, and previously repressed memories and unacknowledged feelings,” Pavlenko notes in Bilingual Minds.

Therefore, she writes, these people may end up associating “anxiety and vulnerability” with the first language and prefer the second language as a defense mechanism.

“They may also describe themselves as frightened, dependent and vulnerable children in the [first language] and as independent, strong, and refined individuals in the [second language].”

Remember those respondents in Pavlenko’s survey who said they did not feel like different people across their different languages?

They made up 26 percent of the pool.

Their responses had a surprising pattern. They said they did feel different when they used their different languages—yet, they saw themselves as the same person regardless of the language they used.

“Different languages allow me different thought structures and possibly different ways of feeling too. But these changes do not affect me deep within where I remain the same person,” one respondent wrote.

Another respondent said, “I feel I have integrated the French side of my character into my English.”

Pavlenko told me this paradox of feeling different when you switch languages while still seeing yourself as one person probably has to do with personal beliefs about the self.

“If you believe there can only be a single self, you will say, ‘Well, maybe I experience that [difference] a bit, but at the end there is only one self.’ If, however, you’re more comfortable acknowledging some kind of duality, some kind of schizophrenia, then you say, ‘Yeah, I do kind of feel different, and I may or may not be at peace with that.’ ”

It’s also customary to alter your personal narrative when you use different languages because as the language changes, so does the audience, Pavlenko told me.

“The narrative changes because you know what the audience expects, what they understand, what they don’t understand, and you adjust.”

It’s the knowledge of the audience that drives the narrative, rather than what actually happened to you, Pavlenko explained.

That’s why the novelist Vladimir Nabokov, who moved from his native Russia to France, Germany and then the United States, famously wrote three versions of his autobiography.

He penned the first version in English. When he started translating it into Russian, he made a number of changes. For example, he added new memories, which his use of Russian had triggered.

The resulting book was so different that he retranslated it into English, with his wife’s help.

“This re-Englishing of a Russian re-version of what had been an English re-telling of Russian memories in the first place proved to be a diabolical task, but some consolation was given me by the thought that such multiple metamorphoses, familiar to butterflies, had not been tried by any human before,” Nabokov wrote in the foreword to the revised English version, Speak, Memory.

Just How Turkish?

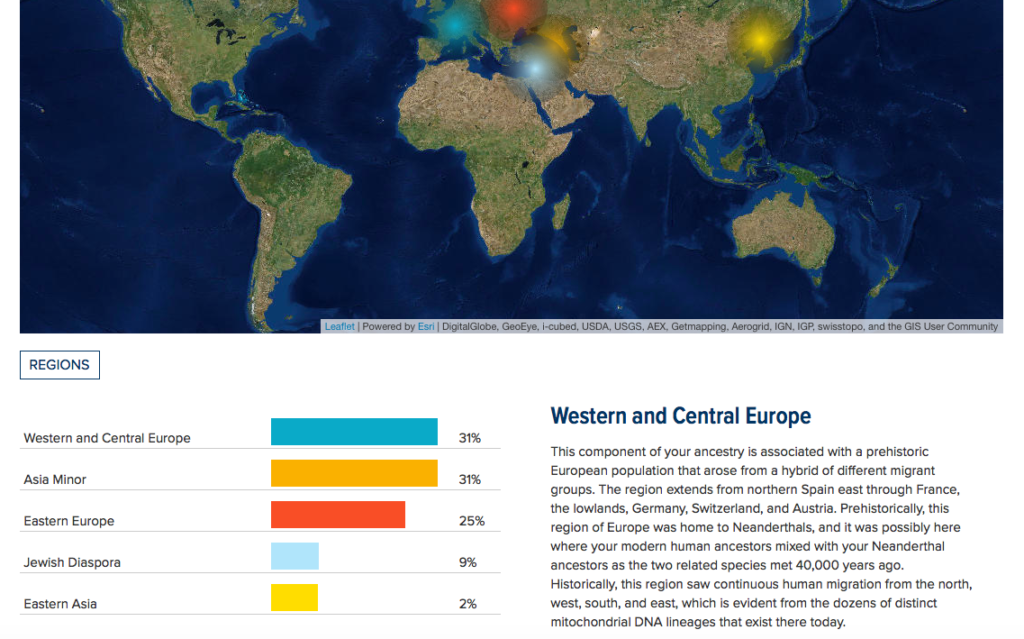

A couple of years ago, I did a National Geographic ancestry test.

It looks like my genes may not be that Turkish.

Only 31 percent of my ancestry comes from Asia Minor—a region made up of the Anatolian peninsula, which comprises much of modern Turkey.

The Asia Minor genetic component appears most often in people from Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and the countries in the Caucasus region, such as Azerbaijan and Georgia, according to National Geographic.

I was disappointed that the Asia Minor component of my ancestry is only 31 percent. All this shame and angst for just 31 percent?

Twenty-five percent of my ancestry is Eastern European. Like other Eastern Europeans, Bulgarians carry this genetic component, but they usually have a higher percentage of it than I do.

Thirty-one percent of my ancestry originates from Central and Western Europe.

Nine percent dates back to the Jewish diaspora, a genetic component common among those Jews who left the Middle East to Europe centuries ago.

Two percent of my ancestry has its origins in Eastern Asia.

Who our genes say we are, who we feel we are, and who we are raised to be can be different things. Ethnicity and nationality are social constructs—constructs created to serve political agendas. Yet, we let these artificial constructs define and divide us.

“But Your English Is So Good!”

I had a dream recently. I was in Turkey, at my aunt’s place.

I was embarrassed that I couldn’t converse with her in Turkish. I responded in English to everything she said. I eventually apologized to her for losing my Turkish.

“But your English is so good!” she said with pride.

There was nothing but love and compassion in her eyes. ♦

ALSO READ:

Shame and Self-Loathing in Brussels

People Mispronounce My Foreign Name But It’s Partly My Fault